Reviews

It was clear, even before the concert began, that the enthusiastic, nattily well-dressed, largely Armenian crowd that gathered Tuesday night at Symphony Hall anticipated a extraordinary evening of music and kinship. I almost felt like I was crashing a huge family reunion. It was the friendliest and most happily expectant crowd I’d seen at a concert in a long time. The first balcony and floor were packed.

Armenia has had an extremely tough time of it historically, especially since the genocide of 1915. This concert aimed to redress the most recent heartbreaking humanitarian disaster and help out 120,000 displaced refugees from the community of Artsakh. It was extraordinary to see the devotion of Boston’s Armenian community of kindred spirits.

The concert, featuring the extraordinary Armenian-born pianist Sergei Babayan, paid tribute to Aram Khachaturian’s 120th and Sergei Rachmaninoff’s 150th anniversaries. The mostly youthful Armenian National Orchestra, conducted by Eduard Topchjan, opened with selections from Khachaturian’s “Spartacus Ballet Suites.” Played with enthusiasm, featuring a multitude of instrumental colors, and rarely performed here, it made for terrific opener. Of the three numbers, Variation of Aegina and Bacchanalia, Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia, and Dance of Gaditanae-Victory of Spartacus, which was a bit rambunctious, I liked the Adagio best; its lovely oboe solos and a prominent harp accompaniment (some composers know what a harpist/critic likes to hear) gave much pleasure. It was hard not to notice that the concertmaster Karen Tosunyan and most of the strings were youngish women sporting four-inch heels and sparkly tops. The episodes moved by with great commitment, and the audience seemed to be enjoying itself. But the best was yet to come.

The phenomenal Sergei Babayan delivered a sensitive, utterly thrilling performance of Rachmaninoff’s 3rd Piano Concerto (Opus 30), making short work of the sprawling concerto’s technical difficulties. It turns out that this concerto, and Rachmaninoff’s solo piano music, are two of his specialties (check out his take on Rach 3 HERE). I first heard Babayan several years ago on the Celebrity Series of Boston with his former pupil, Daniil Trifonov (who appeared impressively just last week again, on Celebrity Series). But at the duo concert, it was Babayan who captured my attention, and I grabbed the chance to see him live again. While he is hardly a household name, he’s won a slew of competitions, and, to boot, his recent duo partner is the great Martha Argerich. Artist-in-Residence at Cleveland Institute of Music for many years, he has been teaching at Juilliard since 2014. I have resolved never to miss him live, although he is hardly a frequenter of these parts.

The ultra-virtuosic concerto had a particular moment of fame when it was featured in the movie Shine in which the pianist David Helfgott is driven to madness by the concerto’s technical and emotional demands. Rachmaninoff wrote it for his own formidably gifted self, though he had trouble playing his own cadenza, and later simplified it. After the brief nerve-wracking first few bars, in which the orchestra commenced at a tempo decidedly different than the one Babayan was anticipating, he came in and played magnificently, with perfectly executed dynamics and lyricism, his magisterial technique almost was thrilling as his tender musicality…and he had no trouble with the demanding first version of the cadenza. Next time he is in Boston, RUN to see him!

When other mortals would have been soaking their hands post-concerto in ice water, Babayan returned to play an important short and vanishingly quiet encore by Arvo Pärt. According to my laptop genie, Pärt’s mature style was inaugurated in 1976 with this very piece, “Für Alina,” that remains one of his best-known works. It is governed by the compositional system that he called “tintinnabuli,” derived from the Latin word for “bells.” The tintinnabuli method pairs each note of the melody with a note that comes from a harmonizing chord, so they ring together with bell-like resonance.” I loved my first hearing. A very moving, soul-cleansing piece. Thank you, Mr. Babayan.

Rachmaninoff’s wildly popular, soul-on-his-sleeve Symphony No. 2 in E Minor, Opus 27 is so beloved because one gorgeous tune just morphs into the next glorious and memorable one. Clarinets must live to play their solos in this piece, and the French horns also notably excelled. I often imagine I am listening to Rachmaninoff whispering in my ear, “If you think this tune its fabulous, listen to this!” The ultra-Romantic 3rd Movement felt sluggish, and balances did not always allow the important solos to bloom in the hall (a problem unfortunately frequent under Topchjan’s leadership).

My publisher reports that the orchestra encored with an armed-for bears take on Khachaturian’s Masquerade Waltz. Topchjan’s insistent rolling arm gestures kept things moving at warp speed and resounding volume.

It takes a huge, committed community to organize and fundraise something as wonderful as this concert. Due to the generosity of the sponsors, all of the revenue from ticket sales supported the humanitarian needs of the people of Artsakh. I love a community that is there to help its own. This concert provided a perfect example of unity and solidarity.

Why – I ask myself – was I so drawn to the Armenian National Philharmonic Orchestra at Carnegie Hall on Wednesday (Nov. 15)? Tangible reasons include the presence of violinist Sergey Khachatryan – one of the best out there – as well as the commercial recordings that have fitfully emerged from that mountainous former-Soviet country. Then there’s the Komitas factor. He was an Armenian priest, musicologist, composer and singer (1869-1935) whose recorded voice I discovered at The Record Shop in Red Hook, Brooklyn: While I was transfixed by the depth of his intensity, the store was in danger of being evacuated because others couldn’t take it,

At Carnegie, I was looking for great orchestral music played from an alternative tradition. Indeed, I found it – but the alternative not what I expected. The program by the Armenian National Philharmonic Orchestra (established 1925 and based in Yerevan) represented Armenia’s best-known composer Aram Khachaturian with excerpts from the ballet Spartacus and his Violin Concerto in the first half, and then, in what became a litmus test for the orchestra’s personality, the Rachmaninoff Symphony No. 2, conducted by longtime music director Eduard Topchjan. The New York appearance felt a bit under the grid. Though the orchestra is on a world tour that includes Montreal and Toronto, the concert was not a Carnegie Hall presentation, but arrived courtesy of something called Classic Music TV. The top two balconies weren’t available for sale. The audience looked like some sort of date night – lots of young-ish couples – and listeners wearing clothes with the kinds of design features you don’t see in the U.S. Unruliness was to be expected. Applause erupted between movements. Cracking down on phone cameras kept the Carnegie ushers very busy. But once the music started, silence set in and attention was complete.

The Khachaturian first half showed that the orchestra was well above provincial status, and would be a worthy edition to Carnegie Hall’s presentations of great orchestras from around the world. Every section had its own kind of homogenous, slightly-restrained smoothness that immediately drew in my ears. Not until the Rachmaninoff symphony did I realize that the strings were using a middling level of vibrato – not so little as to suggest a Roger Norrington performance, but enough that the sonorities seemed to glow from within, as opposed to bristling with surface excitement (as in high-vibrato performances). Much drama was generated by the contrasting sonorities of the different orchestral sections. Dimensions of sound opened up in the Rachmaninoff that immediately began to reveal the inner workings of the music but without the slightest sense that the symphony was being dissected. Anybody who loves this work knows how thematically integrated it is. But this performance particularly revealed such details, suggesting that underneath the lush sonorities is music that is downright rigorous. Incidental solos by English horn and clarinet delivered sounds that were particularly arresting, if only because they were not preceded by and engulfed in the usual thick orchestral sonority. Overall, nothing here seemed forced, and that included the Khachaturian Violin Concerto. Violinist Khachatryan has often struck me as a depressive stage presence when, as it turns out here, he was actually relaxed and releasing the music without any extraneous effort. Tension was not conveyed by magnitude of sound but the concentration of sound. Intensity didn’t come from playing harder but from inner intention. What I can’t explain is the deep wells of sound that periodically came forward from the orchestra in moments where the music truly called for it.

This was not hard-sell music making. And it was only by hearing this concert that I realized how much other recent performances this season oversold what was played. At the New York Philharmonic in recent weeks, Jaap van Zweden conducted the loudest Copland Symphony No. 3 that anyone could remember, bleaching out a good 60 percent of the music details, leaving only a general outline filled out by a wall of sound. Pictures at an Exhibition conducted by Susanna Mälkki showed the difference between loudness and grandeur, the former quality being much in evidence and the latter quality being almost completely absent. And these performances were rewarded with roaring ovations. The Philharmonic players know better and often play as though they do. But the loud performances are what we remember for better and for worse.

Of course, the Armenian orchestra played its own nationalistic music with authority. But flourishes suggesting, say, Arabic microtones, the sort that would be played by non-Armenian orchestra as touches of exoticism sounded perfectly natural here. So it is too in the orchestra’s new BIS-label recording Armenian Cello Concertos whose works by Babajanian, Petrossian and, of course, Khachaturian often have more a folk-based flavor, but never sound like postcard music. One has to ask: Can this orchestra also play Mozart? Sure, and does so as if speaking the music like a first language. The Armenian National Philharmonic Orchestra is all over YouTube in all kinds of repertoire, playing in an charmingly idiosyncratic round hall. Part of the season is full concert performances of opera, including the upcoming Tchaikovsky Queen of Spades. With the linguistic authority of singers trained close to Russia and the ‘inside-story’ approach to Tchaikovsky’s rich orchestral writing, I’ll be checking YouTube frequently for that one.

E.Topchjan

“I grew up in an atmosphere rich in folk music: popular festivities, rites, joyous and sad events in the life of the people always accompanied by music, the vivid tunes of Armenian, Azerbaijani and Georgian songs and dances performed by folk bards and musicians–such were the impressions that became deeply engraved on my memory, that determined my musical thinking. They shaped my musical consciousness and lay at the foundations of my artistic personality... Whatever the changes and improvements that took place in my musical taste in later years, their original substance, formed in early childhood in close communion with the people, has always remained the natural soil nourishing all my work.”

Aram Khachaturian

Last night’s performance by the Armenian National Philharmonic Orchestra (ANPO) was dedicated to the 120th Anniversary and 150th Anniversary of Aram Khachaturian and Sergei Rachmaninoff respectively. Far more surprising to this listener is that the ANPO itself will be 100 years old in two years. And that in this time, they have worked with famed artists from Ashkenazy to Zukerman, have performed around the world, and recorded many disks.

One shouldn’t really be surprised. Armenia, whose kingdom once spread all the way across Anatolia, has produced composers like Hovhaness, Khachaturian, and Penderecki (the latter born in Poland but with an Armenian grandparents), great churches and one of my favorite writers, William Saroyan. Plus, the musical scales, harmonies and melodies are absolutely unique.

Some composers might try to hide this unlikely combination of Arabic/Hebraic/Ancient Greek/Caucasian. But Aram Khachaturian relished it, and his music is totally recognizable. Thus the two works last night seemed familiar–even for those who only knew his “Sabre Dance.”

Obviously the ANPO is made for this music, and under conductor Eduard Topchjan, their individual colors were manifest. What this meant above all were gorgeous strings. The tones were hard (never harsh), they soared when the music demanded, and were otherwise luscious. The wind solos were excellent (no list of the players were included, so I can’t give accreditation.) Brass and percussion, so necessary for the composer, were controlled but always effective.

Maestro Topchjan had two assets, one (what I thought) liability. The assets were his total control of the orchestra and an unerring sense of Khachaturian’s structure. Essential to the composer is orchestral crescendo. No matter how solemn is a beginning (as the Adagio from Spartacus), inevitably the orchestra ascended, fuller, flashier. And Mr. Topchjan managed these moments with nuance and utmost control.

The problem in the Violin Concerto, that Adagio and the following Rachmaninoff was that the slow moments were oh so slow. Almost laggard. Yes, he dragged the ANPO quickly out of the doldrums to the spectacular moments, but his echt‑romantic feelings were prevalent.

Those three excerpts from Spartacus were lovely (Khachaturian is always endearing). The Violin Concerto was super‑elegant.

S. Khachatryan

Like the conductor, violinist Sergey Khachatryan is without theatrics, without Joshua Bell‑like attitudes. The tones coming from his Guarneri del Gesù fiddle were resonant, never showy, always focused in all three cadenzas.

This, though, is a concerto with the highest energy levels. Mr. Khachatryan was vigorous enough, and the Andante sostenuto became ravishingly beautiful after a rather doleful introduction.

That was a crowd-pleaser–and it must have pleased Josef Stalin as well. One difference with Shostakovich. The latter was forced to please Stalin, his music contained codes and cryptic passages. They are as mysterious as triumphant. Aram Khachaturian had few problems with the Cultural Politburo. His Armenian music was extrovert, impulsive and showed his own personality.

Both the Armenian and Sergei Rachmaninoff were born at the wrong time. In the mid‑20th Century, they were unbowed Romantics. The Russian lost some popularity (though it’s soared recently thanks to bravura piano playing). Khachaturian is still considered...well, déclassé in some circles. Nice exotic melodies are not appreciated by “serious” musicians.

The Rachmaninoff Second Symphony is appealing for its soaring melodies, its lush textures and–inevitably–brassy loud finales. Eduard Topchjan caught it all with his fine orchestra. The tempos in the second and fourth movements were suitably exciting, and those final moments were blatantly gorgeous.

I did lose a bet with his encore. I wagered a few dollars it would be “Sabre Dance.” No, it was the other showpiece, the waltz from Masquerade. The audience ineluctably found it ravishing and as lush at it deserved.

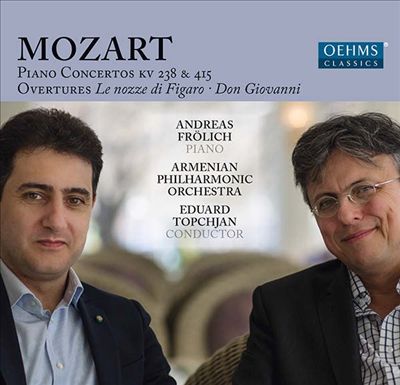

CAN THAT WORK? NO ARROGANCE HERE PLEASE – IT CERTAINLY CAN! ANDREAS FRÖLICH AND THE ARMENIAN PHILHARMONIC OFFER PURE QUALITY.

How quickly one finds one’s own prejudices… Mozart piano concertos from Armenia? Anyone reaching for a good old Austro-German interpretation is really missing out on something. This Armenian Mozart is damn good! And that is not only due to the eternal solo insider tip Andreas Frölich with his accentuated, hyper- exact style that still manages to catch every emotion. It is particularly also because of the wonderfully fresh and alert musical style of the Armenian Philharmonic that leaves an impression of being cheeky and fresh under the direction of Eduard Topchjan even more so that the usual, perhaps slightly Mozart saturated orchestras. You notice that the Armenians have long studied the leading musical theories, without taking on their negative elements. I mean, here is an orchestra that actually has its own sound, which is something only rarely heard. Sirs, I take my hat off to you! These piano concertos show a deep understanding for Mozart’s work and are for me the most exciting thing to pop up in this field in many years. For anyone who doesn’t believe me, have a listen!

Die Diskographie von Andreas Frölich ist bislang geprägt von Kammermusik und Sololiteratur. Mit seinem neuesten Album hat er sich jetzt auf ein Terrain begeben, auf dem die Konkurrenz groß ist: Mozarts Klavierkonzerte. Taktisch geschickt, hat er sich dabei allerdings nicht auf die Schlachtrösser gestürzt, sondern zwei Werke ausgewählt, die nicht so sehr im Fokus stehen, dennoch aber die ganze Bandbreite dessen aufzeigen, was Mozart in dieser Gattung zuwege gebracht hat. Gut sechs Jahre liegen zwischen dem siebten Klavierkonzert und dem 13., das kurz nach Mozarts Ankunft in Wien entstanden ist. Hier treffen musikalisch zwei Welten aufeinander, die unterschiedliche interpretatorische Herangehensweise voraussetzen.

Sowohl der Solist als auch die begleitenden Armenier haben sich intensiv in die divergierenden Ausdruckswelten der beiden Stücke hineinversetzt und schaffen Wiedergaben von großer gestalterischer Stimmigkeit. Die Tempi in den Ecksätzen sind durchweg frisch, das Klangbild transparent. Details in Artikulation und Phrasierung sind sorgfältig aufeinander abgestimmt. Es herrscht ein entspanntes Musizieren, das dem heiteren Charakter sehr entspricht. Erwähnenswert ist das spieltechnische Niveau, auf dem das Orchester aus Armenien agiert. Das offenbart sich einmal mehr, wenn es aus der Rolle der Begleitcombo heraustritt und in den Ouvertüren zu „Figaros“ und „Don Giovanni“ eindrucksvoll demonstriert, dass es den Vergleich mit dem mitteleuropäischen Establishment nicht zu scheuen braucht.

Arnd Richter

This OehmsClassics all-Mozart disc features two fine piano concerti, K. 238 and K.415 together with the overtures to Le Nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni. K. 415 (1782) is notable for having the largest orchestra forces Mozart had employed up until that time. German pianist Andreas Frölich, concert artist, professor and member of the Mendelssohn Trio, Berlin, has an accumulated discography of close to three-dozen discs. Eduard Topchjan leads the Armenian Philharmonic.

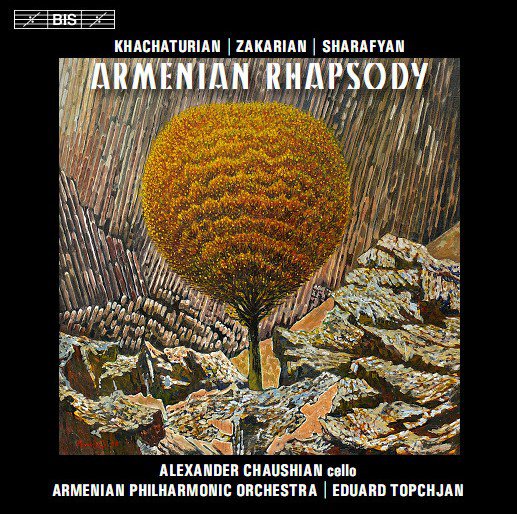

Alexander Chaushian is on sparkling form of this highly enterprising and beautifully recorded CD, Khachaturian’s rarely heard. Concerto-Rhapsody is performed with tremendous conviction, but although this technical tour de force, originally written for Rostropovich, boasts some vintage melodic moments, the score is rather empty, with too much note-spinning. The darker hues of the Monograph for cello and orchestra by Suren Zakarian are far more convincing musically and receive an intensely imaginative performance from Chaushian. Inspired by the concept of the soul in conflict, the work deploys the cello in a high register with shimmering gentle clusters in the orchestral accompaniment. The emotional fervor increases with the cello incanting urgently before ebbing away in a lighter vein.

A similar use of harmonic clusters colours Vache Sharafyan’s suite, which with its ingenious allusions to the harmonic patterns and dance forms of the Baroque travels through a kaleidoscope of indecent timbres. Chaushian is again totally immersed in the vernacular and gives a searingly eloquent rendition. Equally enthralling is Sharafyan’s arrangement of Komitas’s Krunk (Crane) for duduk, piano and cello. As in the Suite, tonally conventional elements co-exist with the oscillating pitches and clusters of Sharafyan’s harmonic language to magical effect.

JOANNE TALBOT

(Armenian Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Eduard Topchjan, BIS Records)

Aram Khachaturian: Rhapsody for cello and orchestra, Suren Zakaryan: Monograph for cello and orchestra, Vache Sharafyan: Suite for cello and orchestra, Komitas: Krounk

Soloist: Alexander Chaushian, cello

Conductor: Eduard Topchjan

One is in mysterious territory from the very first notes of Khachaturian Concerto-Rhapsody. This single-movement work, dating from 1963 and written for Rostropovich, positively drips with the intonation of the Armenia of the composer’ s ancestors- he was actually born in Georgia –though the anonymous notes for this new recording claim that it is in fact less Armenian in spirit than many of his other works. Whatever the case, it is one of those works that clearly has a dimension that relates to extra-European dimension folk traditions at some level, and this is certainly brought out by this powerful playing of Alexander Chaushian. Though it is not heard in concert with any great frequency, there are a number of other fine recordings of this work including more than one by its dedicatee. The couplings here are unique, however; indeed anyone with the slightest interest in twentieth -century music from this remarkable country should not hesitate to invest in this disc.

What the music of Suren Zakarian (b.1956) and Vache Sharafyan (b. 1966) have in common with that of Khachaturian, different though their musical languages are, is a powerful intensity. Zakaryan’s Monograph is a dark, brooding work built from the exploration of the interval of a second, and displaying a tremendously subtle handling of texture and colour. The title of Sharafyan’s for-movement Suite for cello and orchestra is perhaps misleading: it’s a substantial work that, while certainly evoking dance in the middle of two movements, is a long- breathed meditation on the passing of time, as the names of the first and last movements, “Mattinata” and “Postero die” (“the following day”), indicate. Its language is less abrasive than that of Zakarian, but it shares a brooding, mystical quality that suites the cello perfectly.

An arrangement of an arrangement closes this evocative collection. Sharafyan has taken a version of the old Armenian love song Krunk (Crane), made by the revered Komitas, and reworked it for the duduk, the national instrument, solo cello and piano. It’s hauntingly lovely, the perfect ending to this excellently performed and beautifully recorded anthology of rhapsodies.

Ivan Moody

This beautifully performed concert with cellist Alexander Chaushian includes a new work by Vache Sharafyan and also Monograph, an exquisite chamber work by Suren Zaqaryan that begins with an extraordinary three minute piece of free association for cello. Armenian music was never better served.

Michael Church

Cellist Alexander Chaushian is a wonderful artist with excellent technique and musicianship, conveying a wide range of emotions and styles of music. The Armenian Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of Eduard Topchjan is an excellent accompaniment to the cellist, equally capable of evoking many emotions through their technically solid and artistically superior musicianship. Arguably the most enjoyable work on the album is Khachaturian‘s Concerto-Rhapsody, with its lush orchestral beginning that gives way to a cello solo which is rather like, unusually, a cadenza at the beginning of the work. One hears a distinctly non-European tonality (somewhat like Indian classical music) with haunting melodies and a repeated, pleading motif throughout the work. It is emotionally stirring, and both the orchestra and soloist bring out strong dynamic and stylistic contrasts. The orchestra manages to play precisely, and yet the sound is still lyrical and smooth.Chaushian is as agile as a violinist, for he makes the cello seem effortless. Suren Zakarian‘s piece for cello and chamber orchestra is quite a contrast to Khachaturian‘s. From the beginning, with its long, tense, highly vibrated notes, the listener is unclear about the tonality. It’s almost disconcerting, even after the orchestra enters. The orchestra plays a drone tone behind the cello, and sometimes this is quite a trial to hear. Zakarian is working with tone colors and moods, alternating passages where the cello is allowed to sing out (this is quite nice to hear), and low, murky, dark passages. This is no reflection on the musicians, but rather a comment on the accessibility of the piece. The same could be said for moments in Vache Sharafyan‘s Suite for cello and orchestra, where sometimes the cello line is so entwined with the orchestra in the first movement that it is hard to hear, and it can sound rather cacophonous. However, the second movement features light, ethereal strings and a liquid, singing cello, and the third movement, a Sarabande, allows the cello to become impassioned and then dramatically drops into silence. The final piece on the album, Krunk (Crane), is fascinating; it introduces the woodwind instrument called the duduk. The entrancing, mysterious beginning creates a sense of melancholy that pervades the work, and the three voices intertwine so smoothly, shimmering. So while some of the music may not be to everyone’s taste, it is still a wonderful album with unquestionably excellent musicians showcasing the best of their culture. ~ V.

Vasan, Rovi

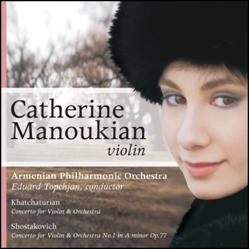

This uplifting performance of Khachaturian’s Violin Concerto, one of the undoubted masterpiece of the 20th century repertoire, comes from musicians associated with the composer’s homeland. The Armenian orchestra’s playing is stylish and rhythmically finessed, with some especially beguiling woodwind. Eduard Topchjan keeps his forces admirably controlled, allowing space for the violin soloist to shine. There are vibrant and vital passages for the orchestral strings, especially after the soloist’s cadenza – launched by an exquisite dialogue with the clarinet- and in the Andante sostenuto, where middle strings play plaintively above pizzicato cellos and double basses.

Canadian-born Catherine Manoukian is an eloquent exponent of this appetising work. Her tone is pure, with nicely understated vibrato, and her playing throughout is gorgeously expressive. The gentle lilt of Khachaturian’s high-flying melodic lines, not least in the berceuse-like Andante, comes across almost effortlessly„ as if the violin were floating on an oriental carpet of air, swayed here and there by gentle breezes, until the spirited finale calls forth a more vigorous tone. All in all, a scintillatingly good performance, splendidly captured.

The Shostakovich begins in sombre vein, with atmospheric orchestral strings. The first movement, shrouded in mystery, is brilliantly sustained. The solo line comes over admirably, not least when engaging in sad dialogue with dark lower woodwind. A gutsy Scherzo follows, before the intense, varied Passacaglia, to which Manoukian’s involvement and restraint lend added power. The prolonged cadenza is superbly executed and the jaunty closing Burlesque is brilliantly played. All in all, an exciting, beautifully recorded disc.

Marquis

RODERICK DUNNETT

***

“The ensemble proved to be a warm-toned, well-disciplined, highly capable body, with, in particular, a string section of burnished tonal sheen.”

The New York Post

***

“The glory of the orchestra is its string section… This was rich, colorful,fullthroated sound, a choir of sound.”

The Boston Globe

***

“The repertoire was obviously chosen to show the orchestra’s strengths … it plays Shostakovich and the rest of its program with enormous impact.”

Joseph McLellan,

The Washington Post